"Some day when the cover-up has ended and all the bulldust has settled,

November 1952, may be marked by historians for something more than the

month in which 20 years of Democratic Party grip on the White House

came to an end.

To be sure, Dwight Eisenhower’s victory of 4 November deserves its

place in the sun: a hero of World War II climbing the final pinnacle

of public service at age 62, the reluctant Republican candidate

drafted into the race by popular demand.

But as Ike – as he was popularly known – celebrated his victory with

friends in a New York ballroom that night, neither he nor the millions

of other voters could have known that two weeks later, across the

country in the desert of Southern California, another American of

almost the same age, would realize a soaring ambition of an altogether

different kind, an achievement more remarkable in its own way than

that of the newly elected president.

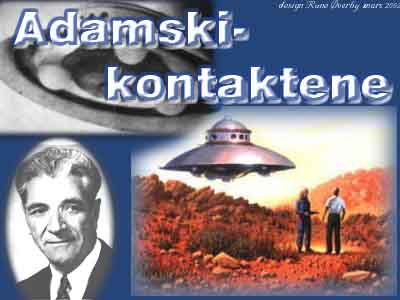

On 20 November, under the distant gaze of six eye-witnesses, a few of

whom were watching through binoculars in the clear desert air, George

Adamski apparently met a man from another planet and communicated with

him for about 45 minutes.

Adamski’s friends, all of whom later swore supportive affidavits about

the remarkable events of that day, had accompanied their pied piper in

a cat-and-mouse car journey on the roads around the dusty stop-over

called Desert Center. It was cat-and-mouse with a difference: the

quarry in this case was a large cigar-shaped UFO floating serenely in

the blue sky, and the stalkers were Adamski and his friends shadowing

the craft in their two cars, waiting to pounce should the visitors

make a touchdown. The seven had been many hours on the road that day

on a UFO-hunting expedition prompted by one of Adamski’s hunches. When

they finally struck gold they were eating lunch on an isolated back

road 11 miles from Desert Center. After the silvery ship had floated

into view their excited leader had headed off into the hills on his

own, hoping for a face-to-face contact. He positioned himself with his

tripod-mounted telescope about half a mile from his friends and told

them not to approach until he signaled.

After some minutes they saw Adamski leave his position and head for a

ravine between two low hills. He approached another distant figure and

seemingly began to talk to him. Through the binoculars that were

passed from person to person his friends saw Adamski and the man

gesticulating to each other as they conversed. Alice Wells studied the

stranger closely and later drew a sketch of a man with long hair,

dressed in a one-piece suit that had a broad band at the waist and was

pulled tight at the wrists and ankles. One of the other observers,

Lucy McGinnis, had seen a small craft come down near where the unknown

visitor had appeared. “They stood talking to each other and we saw

them turn and go back up to the ship,” she said later. The witnesses’

view of the scout ship, as Adamski dubbed it, was not a good one. It

was seen as a bright and sparkling object rising and falling behind

some boulders. They told Irish investigator, Desmond Leslie, in 1954,

that when the ship had left the scene it shot up into the sky in a

brilliant flash. Twenty seven years later McGinnis described it in

more detail to another British researcher, Timothy Good: “…when it

left, it was just like a bubble or kind of like a bright light that

lifted up.

(rø-comment: then seemingly

increasing the vibration-freq.of the whole ship, making it capable

to enter the astral/4d level which is where the planetary jumps

/'travels' happen.)

Then George went out on to the highway and he motioned for

us to come out.” When they reached their leader he was babbling almost

incoherently. “If he was an actor,” said George Hunt Williamson, “then

he was the best actor I’ve ever known. He was out of his mind with

excitement.” Desmond Leslie interviewed the witnesses closely on what

happened next. They described how they had back-tracked with the

breathless Adamski to the scene of the contact, all the while

peppering him with questions. “I seemed to be in another world,”

Adamski later wrote. “My answer to the questions, were given in a daze.”

If his answers lacked clarity, his footprints did not. They were

imprinted clearly in the soft dirt. The group came upon smaller ones

with distinctive markings that the ‘spaceman’ had left. Williamson and

his wife Betty took plaster casts of the best examples. The small

prints led back to the site of the touchdown then stopped abruptly.

Adamski’s detailed account of his meeting with this handsome, human

looking visitor with the shoulder-length hair of a seventies hippie,

is described in detail in the book, Flying Saucers Have Landed, which

he co-authored in 1953 with Desmond Leslie.(link) The key point to be made

about this event and subsequent face-to-face encounters that he and

other credible witnesses reported in the 1950s was that the alien

interaction was taking place on these occasions with human looking

visitors, not Grey-type aliens. Not only were the encounters with

distinctly human types but these ‘space people’ generally communicated

in a benevolent and helpful way. They were concerned with the trends

on Earth, they said, often in plain English. Atomic bomb testing was

their number one concern. The witnesses who came forward to report

these more inspirational contacts were generally rubbished by the

mainstream press. These brave people were flippantly debunked as

wishful fantasists and grouped together under the derisory term ‘contactees’.

The word said it all without the need for enlargement; it had about it

the feel of other “ee” words – devotee, divorcee, debauchee. Their

detractors were not only the news media but ‘mainstream’ UFO research

groups who craved respectability and were terrified that reports of

commonsense, repeat meetings with human-like aliens, who sometimes

talked about the spiritual life, would bring the whole serious subject

into disrepute. If only the NICAPs, APROs and MUFONs – the biggest

research groups – had known that there was no chance that they could

insinuate their way into the good books of the myopic scientific

community, or get a fair hearing from the US government, no matter how

much they behaved themselves. That same government, operating in a

vastly resourced conspiracy, would stop at nothing to suppress and

discredit any attempt to elevate the subject to the level of the

respectable. No amount of hobnobbing in Washington or sneering at the

‘lunatic fringe’ was ever going to get ufology’s unctuous

conservatives on to the right side of the railway tracks.

The

contactees were like coarse gatecrashers at a refined dinner party,

blowhards who wedged thei r seats among the dignified social climbers

and ruined the artful agenda. But the hosts weren’t going to buy the

pitch anyway. No amount of decorous table talk or dexterity with the

cutlery was ever going to give the Donald Keyhoes, the Richard Halls,

Allen Hyneks and Walt Andruses the gravitas that they sought. Like

thousands of other sincere researchers and advocates who devoted

countless hours of hard and thankless work to the campaign for

official recognition, these people were doomed in their noble quest

even before they started. The apparatus that had been erected to lie

and obfuscate the issue could not tolerate a single chink in the

armour of deceit. No compromise, no partial admission was possible

without the integrity of the whole edifice of deception being

threatened.

In the early, romantic era of the flying saucers, the age of Elvis,

McCarthy, I Love Lucy, and delta-winged Dodges, a fascinating duality

of encounter emerged. The most secretive of the visitors – the greys –

who were not much engaged in encounter activity (at that time), were

crashing all round the place. They were furtive and shy but their

flawed technology kept blowing their cover. Their fatal mishaps

virtually monopolised official attention – the crash site clean-ups,

the cover stories, the corpse collections, the alien autopsies, the

reverse engineering of intact craft.

In the early, romantic era of the flying saucers, the age of Elvis,

McCarthy, I Love Lucy, and delta-winged Dodges, a fascinating duality

of encounter emerged. The most secretive of the visitors – the greys –

who were not much engaged in encounter activity (at that time), were

crashing all round the place. They were furtive and shy but their

flawed technology kept blowing their cover. Their fatal mishaps

virtually monopolised official attention – the crash site clean-ups,

the cover stories, the corpse collections, the alien autopsies, the

reverse engineering of intact craft.

By contrast, the talkative and

likeable visitors described by the contactees never crashed their

craft. Their machines were far more reliable. The first group was a

disturbing enigma who left their calling card in a trail of debris and

lifeless bodies. The second were an open book but left no trace, apart

from the stories of those they had met.

The greys were far more credible as aliens. They looked liked aliens

should look – they looked different. They were ‘picture book’ ET’s.

They had wonky eyes and spindly limbs. Encounters with human visitors,

no matter how strong the collateral witnesses or photographic evidence,

were simply never going to cut it. If the right wing of ‘ufology’ was

ever going to move on from ‘sightings in the sky’ and let

flesh-and-blood aliens into the pantheon of dignified debate it was

only ever going to be the greys, especially once abduction activities

by these taciturn visitors stepped up after the 1960s.

And then there was the problem – which must be admitted – that the

most prominent of the contactees seemed to overegg the recipe from

time to time. The guileless millions who thought, in all their

delightful ingenuousness, that one day the truth about UFOs simply

must out, did not count on the quagmire that lay between the rock and

the hard place: on one side a seamlessly organised, taxpayer-funded

cover-up with all the manpower, surveillance tools and disinformation

techniques that the State could muster; on the other side witnesses

‘of the third kind’ with yarns that sometimes fell apart after a good

poke.

The Saintly S camp

The Janus face of the UFO ‘problem’ expressed itself most vividly in

the person of

George Adamski. He seemed to be half holy man, half huckster, a

fascinating blend of the sublime and the slippery. Adamski was two of

a kind. Where one George left off and the other started is hard to say.

But there is a tightly coiled stature here that needs to be released

to its full, awesome measure, and then we need to consider the

banalities of human nature that diminished the man’s standing and

legacy.

Posterity has allowed George Adamski to control his own biography. No

discerning writer sought to pin him down before he died in 1965 and

produce a vigorous and probing picture, especially of the explosive

last 13 years when his fame was world-wide and his photo instantly

recognisable. The scores of acquaintances, friends and family from his

first 60 years – the pre-flying saucer days – have gone. The

biographical sketch in his second book on UFOs, Inside the Space Ships,

published in 1956,

(link)

was penned by ghost writer Charlotte Blodget, a dab

hand at journalistic cosmetics. No doubt under George’s guidance, this

admirer from the Bahamas crafted a hagiographic four pages that

portrayed his life as a patiently compiled spiritual odyssey, from

small town poverty on the shores of Lake Erie to veneration as the

savant of Laguna Beach; Huckleberry Finn with a Polish accent punting

his way across the American Century in a leaky boat, gathering in a

trove of transcendental insights.

None of those who spent years in his presence in the forties and

fifties – which amounted to three or four admirers and his wife –

wrote anything that resembled a reminiscence. He married Mary

Shimbersky in 1917 but she died of cancer in 1954 without leaving

anything for annalists. For some reason a veil of silence descended.

Blodget failed to mention Mary’s death in her biographical sketch

written in 1955.

George’s own airbrushed account of his domestic

arrangements in the 1953-55 period leave her out as well. It was a

shrewd move that helped forestall gossip: indicating the marriage’s

beginning but not its ending served the useful purpose of fudging

Adamski’s unconventional domestic milieu after that time. Mary had

been around for the hard work during her husband’s back-to-the-land

projects in Valley Center-Palomar in the 1940s.

She was apparently a

devout Catholic, which, with George’s reincarnationist views, would

have made for interesting table talk. His move from the esoteric to

the extraterrestrial was a step too far for his wife. Once, she fell

on her knees begging him to stay away from meetings with his space

friends and discontinue his writings on the subject, he later told his

Swiss co-worker Lou Zinsstag.

But George could not stop anymore, he

told Zinsstag, not even for his wife. His hour had, indeed, arrived;

this is what it had all been leading to. Mary’s passing soon after,

had about it the quality of deus ex machina, a providential release

from marital attachments that freed Adamski for more than a decade of

relentless service to his mission. We do know that during his world

tour of 1959 George would flop out his wallet and show Mary’s photo

fondly to friends. Those who saw the snapshot remember her as a pretty

woman. One can imagine that life with George was not a bed of roses

from the word go. The union was childless and George was a rolling

stone. He served with the Army on the Mexican border for six months in

1918-19 (inflated to five years in the Blodget sketch) then drifted

from job to job with Mary in tow.

When finally they came to rest in

California and George had established himself as a full-time New Age

philosopher and teacher, Mary had to put up with two of his female

acolytes living on the premises. Lucy McGinnis signed on as voluntary

secretary to ‘Professor Adamski’, as he called himself, in the

mid-1940s. She worked for him loyally until the early 1960s when,

along with many of his other supporters, she deserted the work as his

tales seemed to get out of hand. Lucy was only ever known to have

given one interview with a writer reflecting deeply on those years

with George.

Alice Wells also took up residence in the 1940s. She was reportedly

part American Indian and one of the small inner circle who helped

clear a plot of stony land in rural California on the isolated hill

road to Mount Palomar. Here, George and his followers established a

small commune, called Palomar Gardens, with subsistence agriculture

and income from a road-side café to provide the necessities of life.

Alice was touted as the owner of the café but diners often got the

impression it belonged to George. She was prominently mentioned in

Adamski’s books as “Mrs Alice K.Wells” but no visitors ever came

across a Mister Wells. George was nothing if not a ladies’ man.

Declassified FBI files indicate there were “four or five” women

working in the café in 1950, which the bureau’s informant felt was not

justified by the level of business.

Late in 1953 George cracked the whip again. The café was sold and the

group resited further up the road and took to their picks and shovels

once more. “We work hard but we are happy,” he wrote with Maoist

simplicity. It sounded like the hippie ideal of spiritual renewal

through fresh air and bracing outdoor activity among the furrows, the

advance guard of the counter-culture. Indeed George’s romantic

collectivist views had been the cause of the FBI’s early interest in

his activities. He and his waitresses at the Palomar Gardens Café

liked to regale diners not only with tales of flying saucers but with

the virtues of the communist way of life. Adamski told the FBI snitch

that “Russia will dominate the world and we will then have an era of

peace for 1000 years.” He honed his powers of prophecy even further,

predicting a flare-up in the Cold War: “Within the next twelve months

San Diego will be bombed.”

Until 1955 there was no electricity at the new “ashram” (visitor

Desmond Leslie’s word) that followed the move from the café. Lighting

was by candle and kerosene lamp. Fresh water came from a stream. Alice

Wells stuck with George through all of this, after fame had turned to

notoriety, and inherited his share in their joint home in Vista,

California. Leslie said that Wells had an “oriental calm”, which seems

to imply she was a woman of few words; certainly she left precious few

for historians.

A young radio technician from Boise, Idaho, called Carol A.Honey

wandered in and out of George’s life and left a frustratingly

incomplete picture. His writing style suggests a rather humourless

man: he once complained to a magazine that people thought his

published letters were penned by a woman. “How they arrived at this

crazy idea I’ll never know,” he railed. Honey came calling at Palomar

in 1957 on a tour of Californian contactees. He was so impressed with

George that he settled in California and served for several years as

Adamski’s right hand man, especially in the outreach programme which

by now spanned the world, and in his bosses’ hectic lecture schedule.

He too broke with Adamski in 1963 over an alleged ‘trip to Saturn’.

(again- George himself did not

understand those trips happend on a vibration raised level, acc.to

the contacts of "Edw.James" as they seemed fully real to him,

which is the case when the 'day-consciousness is focused on to the

astral body' - but for most people brings no memory back from -

but in some cases though as 'clear dreams'- as really are, acc. to

theosofy/+Martinus, memory-parts of what really happens. rø-rem.)

After departing, Honey went on to work in a technical role for Hughes

Aircraft Corporation for many years, and left relatively small

pickings for researchers. His big chance came in 2002 when he emerged

from obscurity to publish a book on UFOs. Followers of crypto-history

held their breath: juicy gossip from an insider seemed in the offing.

Sadly, the large format, soft cover tome was a disappointment. It

dealt only obliquely with Honey’s former mentor.

The most acute observations we have about Adamski from a long-time

friend are those of Leslie, a dashing free spirit who was worth a book

himself. Leslie was the son of Irish baronet, Sir Shane Leslie, and

spent much of his childhood at Castle Leslie, in County Monaghan. Born

in 1921, he was drawn early to the paranormal by the open mind of his

father, who wrote several books on the subject, and by a sighting of a

green fireball in the sky while at boarding school in England. After

university in Dublin, Leslie became a war-time fighter pilot and

survived to celebrate VE Day drinking Pol Roget at 10 Downing St with

his cousin Winston Churchill and his new wife, a Jewish cabaret singer

from Berlin. Leslie had a roguish sense of humour and often joked that

he destroyed many fighter planes during the war, most of which he was

piloting.

The onset of the flying saucer age in 1947 tantalised the handsome

aristocrat and he began researching ancient texts and the writings of

anomalist Charles Fort, fossicking out startling references to

antediluvian flying machines and early UFO sightings. The year 1952

found Leslie hawking a manuscript around London publishers that pulled

together the results of his antiquarian endeavours. Hearing of

Adamski’s desert encounter, he fired off a letter asking if he could

see, and possibly buy, the Californian’s photos.

“He replied by sending me the whole remarkable set of pictures with

permission to use them without fee,” recalled Leslie in 1965. “What an

extradordinary man, I thought. He takes the most priceless pictures of

all time and wants no money for them. Later he sent me his manuscript

humbly suggesting I might be able to find a publisher for it.”

By this

time Leslie had scored a contract with Waveney Girvan, at Werner

Laurie. “After much soul searching Waveney suggested a joint

publication. We wrote to George who cabled the following day before

receiving our letter, ‘Agree to joint publication.’ Here indeed was

telepathy at work. And so the amazing relationship developed!” Adamski

had spoken a lot on the subject of telepathy during his years at

Laguna Beach and said he used a combination of gestures and telepathy

to communicate with the ufonaut at Desert Center.

Desmond Leslie Visits

In June, 1954, Leslie kissed his wife and three children goodbye and

headed off to California to meet the mystery man who had helped make

his book a runaway best seller. He was 33 and Adamski was 63. Despite

the age difference the two hit it off straight away. Leslie’s visit

was “a great joy,” Adamski wrote a year later. “Endowed with a very

interesting mind and a delightful sense of humour, he added much to

our little group here, not only in that he shared our common interests

but also entered into the nonsense which often overtook us when

relaxation from serious subjects was indicated.” To accommodate their

distinguished guest, Adamski and his group rejigged the cramped

sleeping arrangements, easing one of the regulars into a pup tent.

Leslie came intending to visit for a month but stayed on for nearly

three. The air at Palomar Terraces, as the property was now called,

was crackling with excitement. If there was one place on the planet

that a UFO buff would want to be in 1954 it was Palomar Terraces –

electricity or no electricity.

Adamski, who had spent years peering at

the night sky through telescopes snapping impressive pictures of UFOs

when he could get a rare shot at one, was now at the epicentre of

staggering events. He was no longer the patient hunter; the elusive

prey were now coming to him. Leslie arrived to find that Adamski was

involved in an ongoing set of covert contacts with the ‘space people’,

as he called them. Young men, dressed and living as ordinary Americans,

would meet him in Los Angeles and drive him out to isolated spots.

Here, a craft would be waiting and he would be taken up for flights

and meetings; discussions ranged over current events, philosophy,

religion and science. The people said they came from planets in the

solar system, including Venus, Mars and Saturn.

(...as they in fact did- but

they did not say it was not of/on this 'coarse physical dimension', as

they foresaw that the common people could not understand this +

that would be a filter to make this info un-scientific; naive - to

the scientific thinking people who are trapped in the physcal

thinking. But that was also the meaning, as this info will not be

for common people before they have reached a level of

understanding the multi-dimensionality of life. This will probably

not occur before after ca year 2050-2100 for most people. rø-rem.)

The conundrum of their

true planet of origin would remain unresolved long after Adamski’s

passing.

While Leslie whiled away the summer months on the side of Mount

Palomar, Adamski was often ensconced in his makeshift office, which

also doubled as a bedroom, cobbling a diary of these remarkable

experiences into the raw material for Inside The Space Ships. The

British visitor begged to come on one of the contacts.

George would

feel a rising intuitive or telepathic tension and know it was time to

head off on the 100-mile trip to Los Angeles, where the rendezvous

always took place at the same hotel. Leslie hung around for weeks

hoping to get the green light. Finally George brought back depressing

news from one of his clandestine meetings: the aliens had vetoed the

request. “I complained about this rather bitterly at the time,” Leslie

recalled.

Many years later George told Zinsstag: “You know they once

planned to take aboard a young friend of mine whom I very much wanted

to be favoured. But they tested this man in secrecy and found out that

he was still too young…to keep a secret in his heart.” Adamski further

explained that there were many things to be seen in the saucers that

needed to remain a secret. Leslie might have been given the

thumbs-down but there were compensations – the flying saucers would

come to him instead.

In a letter to his wife, Leslie described seeing “a beautiful golden

ship in the sunset, but brighter than the sunset…It slowly faded out,

the way they do.” Another night he got a glimpse of a small, remotely

controlled observation disk, about 2-3 feet in diameter. George had

watched these sensing devices being launched and retrieved while on

one of his space excursions and would go on to describe them in detail

in his book. Leslie was walking up the road returning to Palomar

Terraces after a visit to Rincon Springs five miles away.

“I noticed a

very bright ball of light rising rapidly from Adamski’s roof, about a

quarter of a mile away. It rose rapidly, rather like a silvery-gold

Verey Light, and continued to rise until it disappeared from sight. It

gave the impression of accelerating as it rose. But the following

evening I was to see it at very close range. We were sitting on the

patio in the twilight, George, Alice Wells, Lucy McGinnis, and I with

my back turned facing the doorway. A curious cold feeling came over me

as of being watched, as if someone or something was standing directly

behind me. I swung round in time to see a small golden disk between us

and the Live Oaks fifty feet away. Almost instantly it shot up in the

air with an imperceptible swish leaving a faint trail behind it, then

vanished.

George grinned solemnly. ‘I was wondering when you were

going to notice that!’ I was amazed. ‘One of those remote control

things?’ I believe I asked. He nodded. ‘Well,’ I said, ‘thank God our

conversation’s been reasonably clean for the last half hour,’ and we

all laughed. For George enjoyed a good story and was quite unshockable.

I felt rather smug, like a schoolboy who for once has been behaving

himself when the Headmaster appears silently in the dormitory.”

Michigan resident Laura Mundo reported a similar sighting in Dearborn

at about the same time in the summer of 1954, several months after she

had guided Adamski on a round of lectures and meetings in the Detroit

area. “A small electronic disk came down across the street from my

house one night when I was sitting on the porch.” But Palomar was

still the place to be.

by about this time, other crafts

were "downed" in other parts of USA - and the military were soon on

the place, securing it - before taking the crafts to secret bases-

as picture her is to illustrate. they moved those downed crafts at

night - but under cover this picture only made to show the idea

McGinnis was lying down in her room one afternoon when for some reason

she decided to get up and go outside. “As I got out the door I looked

up,” she told Timothy Good, “… and here was this great big saucer-like

thing. I was amazed! As I looked up I could see through it )*. It was two

stories: you could see the steps where they would go up and down.”

Good recorded McGinnis’ recollections after tracking her down in

retirement in California in 1979. He found her to be an “intelligent

and highly-perceptive lady.” In her Palomar sighting McGinnis saw

people inside the saucer. “I don’t remember how many people I saw but

they were moving around. It seems to me they had kind of ski-suits,

fastened around the ankle…Then suddenly it started just drifting away.”

)*

("I could see through it..."- yes not fully physical; materialized

or partly now/still on "next level"- rø-rem.)

Lucy McGinnis, Alice and George earned Desmond Leslie’s affection. “I

came to love and respect them as I found, by the quality of their

lives, their actions and reactions, their simplicity and their mental

and spiritual values, they were what one would call ‘good’ people; if

anything, rather better than the average,” he wrote.

“A strange summer. Three months on the side of Mount Palomar with the

enigmatic fascinating, at times infuriating, Mr Adamski. Lovable,

provocative, evasive at times; and at other times overshadowed by a

profundity that was quite awesome. You had to get him alone and

relaxed to discover this deep inner Adamski….one often had the

impression there were two people in that fine leonine body, the little

Adamski, the burbler which always shoved its way to the foreground

when the crowds gathered, talking non-stop…Then there was the big

Adamski, the man we came to know and love, who appeared only to his

intimates, and once having appeared, left them in no doubt they had

known a great soul. The Big Adamski spoke softly with a deep beautiful

voice, incredibly old, wise and patient. Looking into those huge

burning black eyes one realised that this Adamski had experienced far

more than he was able or willing to relate.”

In this Big Adamski,

Leslie wrote another time, “I several times glimpsed the presence of a

Master, and I was always sorry when the curtain came down again and

the worldly mask obscured him.”

Worldly Mask & Otherworldly Visitations

The worldly mask included a moderate appetite for drinking and

smoking. Adamski’s tastes in alcohol were catholic but he preferred

Screwdrivers before his lectures because vodka could not be smelled on

the breath. But, still, there was nothing excessive about his drinking;

it lay within the bell curve. He had an endless store of ribald jokes

and stories, which he didn’t mind telling in mixed company, perhaps as

relief from the stifling expectations that others had of him. Society

hostesses gave their famous guest extra latitude. “Oh George,” said

one through a forced smile over the dinner plates in Auckland, “that

one went a bit too far!” Adamski also used knock-about humour as a

leveler in masculine company, the macho combination of exaggeration

and self-deprecation.

In 1958 he told two visitors to Palomar Terraces

that the Royal Order of Tibet, the name he gave to his theosophical

movement at Laguna Beach in the thirties, had been a racket to get

around Prohibition (which had stretched from 1920 to 1933).

“It was a

front,” he bragged. “Listen, I was able to make the wine. You know,

we’re supposed to have the religious ceremonies; we make the wine for

them, and the authorities can’t interfere with our religion. Hell, I

made enough wine for half of Southern California. In fact, boys, I was

the biggest bootlegger around.”

The worldly mask also included a propensity to invent and fabricate

under the fuel of a viral ego. Quiescent for the most part, this

bacillus flared up from time to time and helped bring Adamski to the

brink of self-immolation. When called to account on these falsities he

often responded angrily like a man betrayed, digging himself deeper

with further evasions and false accusations.

Therein lies the supreme

tragedy of George Adamski. His truthful tales were incredible enough

as it was. They couldn’t bear the further burden of embroidery. They

demanded an unbending integrity of the teller if they were to have

even the faintest hope of a wide currency and regard. All that destiny

demanded of the man was that he stuck to the truth. It was that easy.

No one begrudged him a quick slug before a lecture, a smoke, a

masculine expletive or an off-colour joke. No one cared if he had an

eye for a pretty face, an interest in the occult, or fudged his CV to

hide an embarrassing episode. That was all part of being human. But he

did have to stick to the facts. That was the irreducible minimum: a

no-risk investment in personal integrity. It carried no known costs,

emotionally, spiritually, physically or financially. It was a

no-brainer. But it was not to be.

Within months of the Desert Center contact, Adamski was claiming in

lectures that his speeches had been cleared by the FBI and Air Force

intelligence. This canard was an act of poetic licence arising from a

meeting he had had with representatives of both organisations on 12

January 1953. At that meeting, which had been held at his request,

Adamski spoke about a number of UFO-related items, including his

recent desert encounter. Files released by the FBI to researcher

Nicholas Redfern show that Adamski had then magnified this cosy

relationship with officialdom into an indication of endorsement in a

speech to a California Lions Club on 12 March. Agents of the FBI and

Air Force Office of Special Investigations visited him at the Palomar

Gardens Café and “severely admonished” him for this false claim. They

insisted he sign an official document in which he declared his speech

material did not have official endorsement. One copy was left with

Adamski and other copies were circulated to FBI director, J.Edgar

Hoover, and three branch offices.

In December, Adamski was at it again.

He had doctored the letter the men had left behind and shown it to the

Los Angeles-based Better Business Bureau to make it seem that the FBI

and Air Force signatories had backed his claims. Special Agent Willis,

of the San Diego FBI, was told to take a team back to Palomar to well

and truly extract this thorn from their side. Willis was instructed by

HQ to retrieve the offending document and “read the riot act in no

uncertain terms pointing out that he has used this document in a

fraudulent, improper manner, that this bureau has not endorsed,

approved, or cleared his speeches or book, that he knows it, and the

Bureau will simply not tolerate any further foolishness,

misrepresentations and falsity on his part.”

George had a cheek

alright – fancy playing MJ-12 at their own shifty game – but his

future hung in the balance. A court appearance for fraud or forgery

could have ruined his promising career as a controversialist. But

head-strong Hoover was not taking guidance from any other shadowy

spooks operating on his patch: he decided not to prosecute.

We don’t have an FBI account of the roasting that Special Agent Willis

and his companions gave George, but we do have the latter’s

self-serving version written several years later as part of an article

valiantly titled “My Fight with the Silence Group”. In this account,

George creates an innocent-truthseeker-does-battle-with-men-in-black

scenario. “…I was visited by three men, two of which I had met

previously,” George wrote, “but the third was a stranger. It was he

who took the role of authority and directly threatened me demanding

certain papers I had, for one thing. Some of these I gave him and was

promised their return, but this promise was never kept. Since I did

not exactly understand to what he had reference, I did not give him

some of my more important papers. There is no need denying that I was

frightened. Before they left I was told to stop talking or they would

come after me, lock me up and throw the key away.”

(This was seemingly at a time

'they' had already decided on the ufo-coverup, and the MIBs came

into action worldwide - but most of them in the USA? Acc.to talk

of BILL COOPER - the MJ12people were in the beginning very

confused what to do with the saucer-problem. Here

talk on that in mp3- same also

on youtube. rø-rem.)

Wily behaviour notwithstanding, the space people stuck with their man.

Wherever George went the flying saucers followed. Those who spent any

time with Adamski had amazing experiences. When he circled the world

in 1959 playing to packed houses and showing impressive movie footage

that he had shot, his escorts were frequently treated to lavish aerial

displays. The four weeks he spent in New Zealand were a case in point.

One day traveling by car between two engagements, Adamski and his two

kiwi companions were accompanied on part of their rural journey by

five pinpoints of light high in the sky which left vapour trails. The

five trails “seemed to keep pace with us,” Ken Pearson wrote later,

“connecting the various clouds on the way.” The driver of the car,

Henk Hinfelaar, said that Adamski accepted the aerial ‘escort’ as a

natural thing; he looked at the trails and said casually, “Oh yeah,

dat’ll be de boys.” A check later with air traffic control indicated

no known air traffic in the vicinity at that time.

Two nights later

after an Adamski lecture in a small town, the wife of one of the men

who had been in the car watched a disc manoeuvre above the lecture

hall. This was small potatoes compared with a sighting a few days

later that two other Adamski escorts had in the town of Taupo. After

passing George on to a new set of hosts taking him further on his tour,

Bill and Isobel Miller lay on their backs in a lake-side park watching

“dozens” of saucers zipping around high in the sky. Bill Miller

qualified his bold claim to a local newspaper – “We could have seen

the same ones twice.”

Being around Adamski was a passport to the

paranormal, right until the time of his death. Ingrid Steckling, who

together with her husband, Fred, spent considerable time with him in

the last two years of his life, reflected on that amazing period: “I

can’t even tell you how many scout craft or spacecraft we have seen…because

I don’t think anybody would believe it.”

‘The Boys’

Yet, ironically, it was not so much the sightings in the sky or

Adamski’s space trips that most tantalised his supporters: it was his

assertion that he met the space people regularly and furtively in

everyday society, and especially when he was on the lecture circuit.

It was to place himself in the best possible position to exploit these

private encounters that Adamski insisted on staying in hotels rather

than private homes. This was a strict injunction that all his lecture

organisers and hosts had to observe; when they broke this rule – as

happened occasionally – he made his annoyance clear.

The most amusing

example of an accommodation foul-up occurred in Australia in February

1959. “At the airport, behind a barricade of people waiting to meet

him, in the front row was a social woman, and as I remember, wearing a

large flowery hat,” wrote Roy Russell later. “George was to emerge

from a room, walk across the front of the barricade and into a private

room where we would meet him. None of us had met Adamski. What should

we expect?….We were released from our apprehensions when George

Adamski finally came through the door formally dressed in a grey

business suit, who took one look at the barricade, and on sighting the

woman in the large flowery hat quickly made his way into the private

room and said, ‘Get me away from that bloody woman!’ They were his

first words to us on Australian soil. They sounded wonderful. We were

dealing with a bloke that an Aussie could understand…This woman we

later learned had visited Adamski in America and he’d not taken kindly

to her persistent visits…We then had to tell him that that woman’s

home was to be his accommodation while here. Sydney had broken the

main rule…”

The “main rule” existed because Adamski had come to live for his

meetings with the visitors. These extraordinary exchanges sent him

into a state of near euphoria. His most deeply observant host, Lou

Zinsstag, of Basle, implied in her reminiscences that Adamski had

elevated his relationship with the space people to a level that

relegated his earthly associations to second class status.

One is left

to ponder whether he over-romanticised his alien interlocutors. Was

his ardent evangelism the price that he knew had to be paid to earn

the prized meetings? Zinsstag spent a total of six weeks with Adamski

during his European trips of 1959 and 1963, and has left us a treasure

trove of acute and multi-layered observations about the enigmatic

companion she guided through three countries.

“I confess that

sometimes I was hurt by his impersonal casuality with which he treated

not only passing guests but also Dora Bauer and myself,” she observed

after his death. “He never was much interested in people – not in

those of this planet, at any rate. And although he wanted me to be

around every hour of the day I felt that this was not out of

friendship, he simply needed me.”

On his first morning in Basle, in

1959, Adamski had been in a “splendid mood,” according to Zinsstag.

“‘Do you notice how happy I am?’ he said, beaming.

‘Yes’ I said, ‘but

why?

Did you have such a good rest?’ ‘Yes indeed I had a good rest but

in the morning I had the visit of two of the boys, they came to my

room at nine o’clock.’ I was quite flabbergasted because I knew what

he meant by this. It was his way to call his extraterrestrial friends

‘boys’ when he was pleased. It was hard even for me to believe him at

that moment but he insisted that there were quite a few in Basle at

the moment. On several mornings of the same week he told me the same

story and so I decided to check on it. I asked the hotel manager as

well as the portier whom I knew well, if Adamski did indeed have

visitors in the morning. ‘Yes’ both men said, ‘there are several men

coming around 9 o’clock, but never more than two at a time.’ I felt

that they were wondering about it. Of course, I could not enlighten

them.”

One afternoon she got a good look at one of the mystery men. Zinsstag

had left Adamski in his hotel room for a two-hour nap and retreated to

a sidewalk café downstairs. “All tables but one were empty. There, a

young man was sitting with a Coca Cola bottle and a glass in front of

him. He looked very distinguished, well dressed, with his dark-blond

hair neatly cut and brushed down over his forehead… His skin had a

strong sun-tan and his eyes were hidden behind large sunglasses…he

looked very intellectual.” Zinsstag tried to guess his nationality.

“I hesitated between American, Swede, Swiss, while I took a seat at a

table at some distance.” As she started on her drink, Adamski appeared,

smiling and light-hearted. “Not so fast, Lou, not so fast!” “I was

much astonished to see him at this moment ….When, twenty minutes

earlier, he had left me he had looked very tired. Now, he stood in

front of me, fresh and wide awake, his eyes sparkling with pleasure.

However it was easy to see that his smile was no longer directed at me

but at the man sitting behind me….Adamski also ordered a Screwdriver

and kept on smiling. After a while the stranger got up, leaving the

open café and crossing the almost empty street, very slowly, while

greeting George and me with a most friendly and prolonged smile. No

word was spoken. When he had disappeared from view I turned to George,

urging him to tell me if he was one of the ‘boys’ who used to come to

his room in the morning. ‘Yes,’ he answered, ‘now that he has left us

I can tell you that much.’ He looked very pleased.

Of course, I had

guessed that a lively telepathic ‘conversation’ must have been going

on behind my back, but what impressed me most, was the fact that the

stranger seemed to have made George come down to where we sat. Adamski

confirmed that he had already slept but was wakened up. ‘I did not

know who it was or why he did it, but I followed the summons. It was

just one of those hunches, you know.’ Most unfortunately, I did not.”

*

One of the New Zealand tour organisers got a shot at George’s

undercover escorts. She was waiting for him at Auckland airport on his

return from a flight to a southern city. “I noticed two good looking

young men with fair hair disembark from the plane among the passengers

and walk across the tarmac,” she said later. “They could have been

brothers but I didn’t pay too much attention, apart from notice that

they smiled at me as they approached the gate. George was the last

person off the plane and when he got to me he said excitedly, ‘did you

see de boys?’” The woman said she let out an unladylike exclamation as

it dawned on her that she had missed out on a unique opportunity. By

the time they got into the terminal the men had disappeared, to her

great regret.

Adamski’s whole organising committee in Auckland might have spent an

unwitting few hours with one of ‘the boys.’ George advised them that

they had been ‘checked out’ by the space people before his arrival.

Thinking back on the months preceding Adamski’s visit, committee

members came to the conclusion that the stand-out candidate was a fair

complexioned young man of indeterminate race who had joined one of

their afternoon meetings. This young man had arrived out of the blue

at the home of two of the members, shortly before their departure for

the meeting. He claimed to have the same surname as theirs, was

passing through Auckland from overseas, and believed they were related.

The couple had been pleasantly surprised by his arrival and asked if

he would like to accompany them to the meeting. He was enthusiastic

and came along. The visitor was quietly watchful at the gathering,

apart from making one or two enigmatic comments. After that day his

impromptu hosts never heard from him again.

The concept of a clandestine ring of visitors from off the planet

living quietly and watchfully in terrestrial society holds a sublime

fascination: the ‘secret agent’ genre taken to its orbital extreme.

The mind conjures with the problems – the ever-present danger of

detection and exposure, the difficulty of obtaining fake papers, the

mundane chore of getting your hands on cash. Epigrams abound – Goodbye

socialist utopia; welcome to Struggle Street!

Those Coca Colas don’t

grow on trees. In fact, welcome to the real world, buddy! Lou Zinsstag

gave Adamski pocket money, but never saw him spend it. She finally

understood from a remark he made that he had given it to ‘the boys.’

Perhaps there was a humorous downside to the inspiring meetings: “…that

just about wraps up our treatise on telepathy, George. Oh, by the way,

you haven’t got a dollar you can spare?” Zinsstag didn’t begrudge the

money that she and George had forked over: the young man in the café

had been a charmer. “He looked so very nice,” she told a British

audience in 1967, “that I was quite happy to think that it was he who

had got my money.” Bob Geldof, your new mission should you wish to

accept it….

Adamski told Roy Russell in Brisbane that the space people had once

been involved in the British shipping industry in order to generate

funds for their undercover operations. He seemed to imply that they

had moved on to other money-earning ventures in America. Carol Honey

may have come upon one of their more modest forays into capitalism

when he accompanied Adamski on a lecture tour in the Pacific

north-west in August, 1957. “We had just finished breakfast…and were

driving up the road towards our next stop, Grants Pass, Oregon. I was

driving in my car and chose the route myself,” Honey wrote in 1959.

“We passed a small café and as we went by George had a ‘telepathic

hunch’ to stop. I couldn’t understand this as we had just eaten a

short time before. He insisted so I turned the car around and we went

into the café. As we entered the door a very small blonde girl

approached and George acted as if someone had hit him on the head with

a hammer. In fact, he acted so strange about her that it caused me to

get suspicious.

After she showed me that she was reading my every

thought, it finally dawned on me that she was probably a space person.

She looked from a distance as if she was about 12 years old. Close up,

however, she looked much older and I remarked to Adamski that I

thought she was about 45 years old. I had been looking her over pretty

close and when she let me know she was reading my thoughts I was very

embarrassed. She didn’t identify herself to George in any way and

after his coffee and my pie we left and continued on our journey.

George was silent for quite a ways and appeared deep in thought.

Finally I told him I thought this girl was one of the space people

living and working among us. He agreed but said he wasn’t absolutely

sure…”

The two men continued on to Seattle, Washington, and stopped in

a motel for the night. The next morning the phone rang in their room

and a man told Adamski: “Good morning. I called to tell you that you

and the young man were both wrong. The girl you met in the café was

not 45 years old…” Honey recounted that the caller advised that he had

called to relieve George’s mind about a couple of other things in

relation to the woman, and he “let us know that they had given George

the telepathic impression to stop at that particular café. We found

out that the café was run by space people, as a way of supplying food

and funds for those who came down among us on a mission and might need

spending money to get around. Also other space people were in the café

at the time we were there.”

The highly credible and well-documented “Ummo”(link

to p-point intro on that case) contact case in Spain

in the 1960s and 1970s showcased another example of human-like

visitors who apparently set up shop in order to carry out in-depth

cultural study from within. The visitors disclosed a mine of

information in scores of communications to a restricted network of

correspondents, mainly in Spain and France. They seemed to seal their

authenticity in a pre-announced and much photographed flying saucer

fly-by in the Madrid suburb of San Jose de Valderas on 1 June, 1967.

This sensational incident was headlined the following day on the front

page of the daily newspaper, “Informaciones”.

By comparison with

Adamski’s taciturn network, the Ummo infiltrators were surprisingly up

front about how they had operated. There is some evidence that they

financed their lifestyle by bringing in diamonds from off the planet

and feeding them unobtrusively into the world gem trade. Their numbers

appeared to peak in the late 1960s when they said they had nearly 90

observers in place. While the Ummo visitors’ primary focus was on

Spain and a handful of Spanish-speaking countries in South America,

they mentioned that they also had had people in France (their first

point of infiltration in 1950), Denmark, West Berlin and Australia

(Adelaide), among others. In the Middle East crises of 1967 and 1973

when Arab-Israeli conflicts threatened to escalate into a superpower

confrontation, the Ummo visitors took fright from their probability

calculations of nuclear war (38% in the 1967 crisis) and were

temporarily evacuated, in pick-ups that occurred in Spain, Brazil and

Bolivia.

The Ummo visitors maintained that they had tentatively

identified two other groups of human-looking extraterrestrials living

secretly in Earth society. The motives of the other groups, they wrote,

indicated “no negative character”.

Exit The Boys

George Adamski might have lived for his meetings with the boys but he

deserved every minute of whatever it was they gave him. In his old age

he had taken on a global mission, the likes of which no one had ever

conceived let alone initiated. To be sure, it gave him the fame that

he relished but it also brought ridicule and hard work. Not a letter

went unanswered. Speaking invitations were generally accepted. He

stayed on after lectures, talking to the stragglers until late in the

night.

“I sometimes wondered if he ever slept,” said a much younger

host who was run off her feet. At an age when most people were taking

it easy, Adamski had signed on for the toughest job in the world.

Dwight Eisenhower had come to his empyrean with a cast of thousands at

his beck and call. Adamski had a couple of committed volunteers at his

elbow and he was about to lose those.

Some time in 1960 or early 1961, his space contacts came to an end.

George never admitted it. His statements on that matter are

contradictory. Reading between the lines the joyrides in space had

probably petered out in the 1950s, and contact after that had been of

the ‘street corner’ variety. We don’t know why communication was

broken off; there has been much speculation among those with an

interest in this recondite borderland: Adamski had spoken out of turn;

he had breached a confidence; Phase One Contact had come to a natural

end… Whatever it was it hit the 70-year-old dynamo hard. He was left

with the mission but not the pay-off. By now he was living in the

sea-side town of Carlsbad, north of San Diego, with an enlarged

retinue.

Alice Wells was, for the record, his “housekeeper”, Martha

Ulrich, a retired school teacher, was a keen assistant, and Lucy

McGinnis was still in the picture, taking his dictation, massaging his

clumsy syntax into articulate, mistake-free letters on a manual

typewriter, organising his tours, laying down the main rules. Carol

Honey had taken up employment with Hughes but was still in close

liaison from his home up the coast in Anaheim. He took care of

George’s ghost writing, publications and newsletter production. With

‘the boys’ withdrawing from the scene, not only had Adamski lost the

buzz he got from their company, he lost their steadying advice. “Many

of the meetings I have had with our visitors,” he wrote in 1960, “have

dealt mostly with my own problems and possible solutions.” Now he was

on his own with a self-imposed, world-wide mission and a following of

expectant readers and representatives hungry for the next revelation.

It was McGinnis who noticed the change first and then Honey followed.

George began channeling ‘Orthon’, the name Adamski had given to the

Desert Center spaceman. “I was present, along with several others as

witnesses, when Mr Adamski went into a trance state and claimed Orthon

was talking through his vocal chords,” wrote Honey later. “He taught

against this very strongly for many years but then he started doing it

himself. He said it was different in his case, all the others were

fraudulent, but not him, he was genuine.”

Adamski took to using an

occultist’s cliché – a crystal ball – to conjure up the appropriate

visions. Late in 1961, McGinnis quit after 14 years. This was a blow

that George would never fully recover from and he knew the scale of

the disaster. As late as May, 1963, he was begging friends to write to

Lucy and plead with her to return. When she walked out, the quality of

his letters declined and his thoughts on paper were often muddled and

contradictory. There was no one to counsel moderation in the bitter

ructions that were to come, no one to take the sting out of Adamski’s

written broadsides against those who split with him. McGinnis wrote a

gracious and non-committal farewell to the network of co-workers.

“Please understand that this separation is due only to the urge within

me to practice that which I have preached for so long a time. GA’s

experiences through the years I was with him, those reported in

‘Flying Saucers Have Landed’ and ‘Inside the Space Ships’ and our

innumerable letters I will support so long as I live. I was a witness

to his first contact, remember, and I could never denounce that which

I know to be true. Understandably, GA was very upset by my decision.

It hasn’t been easy on any of us. Yet, the urge within me is so strong

that I can no more disregard it than I can stop breathing and continue

to live.”

At the start of 1962, Adamski announced to co-workers that he would

soon make a trip to Saturn to attend an interplanetary conference. At

the end of March he declared that the journey had been successfully

carried out over a 5-day period. On some of the days he was alleged to

have been away Honey knew for a fact that Adamski had been sitting on

his recliner in Carlsbad rather than hurtling through outer space. (

*)

( *see on this

time-confusion etc. on

http://www.galactic.no/rune/venuscont2c.html)

How

did he know? Simple – “…I was with Adamski part of the time…,” he

wrote later. The puzzled ghost writer nevertheless interviewed George

with a straight face and dutifully wrote up an account of the trip

that won his bosses approval and signature. It was a syrupy concoction

of ‘space brother’ schmaltz. The recipe had not so much been

over-egged as over-sugared. Saturn was a planet of fountains and

flower-strewn highways. The superlatives flowed endlessly in a 16-page

gusher: “…the city and surrounding country was beautiful beyond

description…their architecture is beyond anything of our imagination….it

could be considered as heaven itself….the people live as one big

family….one could feel the perfect harmony….the vast beauty which I

witnessed….music seemed to be coming from the fountains, ceilings and

walls, such as never is heard on earth…”

The cloying romanticism of

the account, which Adamski circulated to his followers under the title

“Report on My Trip to the Twelve Counselors Meeting of Sun System”,

wears thin by the second page and it requires a Phenergan to persist

reading to the end. George had been on a far journey alright. The

account’s patent lack of credibility demonstrates the extent to which

Adamski had descended into a mental, intellectual and ethical fog

during this period. Some observers have suggested that the Saturn trip

was an out-of-the-body experience, or a hypnotically-induced fantasy

perpetrated by disinformation agents who had masqueraded as space

people. Lucy McGinnis’view was more prosaic. She told Timothy Good

that Adamski’s oversized ego was the problem. He was simply lying to

pump up his ego, which had taken a knock by the departure of the space

contacts. When the Saturn report reached the international network,

Adamski’s following began to crumble. The view from the inside was

worse.

Later in 1962 he wanted to get into fortune-telling. “He asked

me to publish in my newsletter that he would give an analysis of

photographs for $5, a recent photo and the person’s date of birth,”

Honey wrote. “I refused to do this. He claimed he was shown how to do

this on his ‘Trip To Saturn.’ I could not go along with his new idea

and told him I couldn’t understand how the ‘brothers’ could propose

such a thing. He replied he couldn’t understand it either but he

trusted them and they wouldn’t let him down.” Other hare-brained

schemes were cooked up.

In September, 1963, Honey cut his ties with

his once revered preceptor. Adamski embarked on a campaign of

vitriolic recrimination, savaging Honey and other departing followers,

including McGinnis, heaping the blame for the blow-out on everyone but

himself. Cosmic brotherhood, his tedious mantra from the rostrum, went

out the window on his home turf.

1963: Sense and Non-Sense

It is a biographer’s duty to gather together disparate strands from

time and space and weave them into a coherence that is both just to

the subject and convincing to the reader. The years 1961-62 can be

slickly portrayed as a period of befuddlement and desperation, an

atavistic reversion by Adamski to expedient lying and posturing.

Whether that would be a fair judgment is uncertain. However, it is

from the start of 1963 that Adamski’s life evades coherent

interpretation. The suavest of analyses fails to come to grips with

what was happening. Different friends saw him in different lights.

There was a bipolarity to his behaviour and the persona he projected.

To add to the confusion the space people returned.

The evidence is

strong that they reopened their contacts in 1963 and, on occasion,

their morale-boosting aerial displays as well, which George copiously

filmed with his ubiquitous 16mm camera. Some of his best movie footage

was shot after this date. There is a savage irony here: his closest

supporters are deserting their man, believing him to have lost his way;

“the boys” who deserted him – the mystery men who are the litmus test

of his legitimacy – are returning. Perhaps historians of the merely

terrestrial kind are doomed to frustration trying to figure out these

cross-currents. After all, we are dealing here with a man who was

privy to the most profound and unfathomable hidden knowledge.

In 1963

he confided wistfully to Zinsstag, “My heart is a graveyard of secrets.”

The iceberg metaphor is unavoidable: nine tenths of the information we

need is below the surface, hidden in the disciplined recesses of a

man’s soul – as well as in the unreachable archives of a distant and

nameless society. More accessible earthly chronicles are available

that might one day shed extra light: a partly finished fourth book and

a daunting cache of 60 reel-to-reel audiotapes of talks, lectures and

interviews that Adamski gave. One day a biographer with qualities of

patience and self-punishment will trawl through this archive,

filtering it for fact and fiction. It won’t be an enviable task.

In 1963 the confused signals that Adamski gave out can be tracked in

the recollections of his two good friends in Europe – Zinsstag and

Leslie. He arrived in Basle on 23 May in the mid-point of a European

speaking tour. When Zinsstag asked if he was still in touch with the

Boys, George gave an opaque and defensive answer. “His voice…sounded

unnatural…as if coming from a defiant child, provocative and stubborn.”

That evening she noticed changes. “I felt that he was playing the part

of a contented lecturer while underneath his countenance was a

lingering precariousness. This did not manifest itself, as I would

have expected, in reluctance and caution, but in an unexpected

somewhat naïve boastfulness. Some friendly newcomers who joined us

received flippant answers to their polite questions, and they soon

left our table.

George seemed to have lost his remarkable faculty to

listen attentively and to answer carefully. I felt truly unhappy on

this first evening.” Things improved and the old George returned over

the next few days. Zinsstag and Belgian co-worker May Morlet took

their VIP to Rome for an appointment with the ailing Pope, John XXIII.

The pontiff was in the advanced stages of cancer but George was

determined to deliver a small package that he carried. This had been

given to him some days before by one of the Boys in Copenhagen and

contained a message from the space people to Pope John. Adamski had

been advised of the time to report – in front of St Peters at 11 a.m.

on 31 May. This astonishing mission was vintage Adamski – preposterous

drivel, with the madcap possibility that it was true. George had

played many walk-on parts in the Theatre of the Absurd and this would

be just another.

Would it end in laughter or ovation? “Slowly we

walked up the broad central stairway, looking around,” Zinsstag

recalled later. “Within a few minutes George cried out: ‘There he is,

I can see the man’….swiftly he descended the steps, turning to the

left. I had looked to the right because I expected him to be admitted

through the well-known gate where the Swiss guards were posted. Yet,

without any hesitation, he walked to the left of the Dome where I now

noticed a high wooden entrance gate…with a small built-in door. This

door was partly opened and a man was standing beside it, gesturing

discreetly to George. He wore a black suit but not a priest’s robe.”

George slipped through the opening and it was closed. When the women

returned in an hour’s time, as per George’s instruction, he was almost

leaping up and down with joy, much as he had done 11 years before

after another outrageously implausible meeting in the desert of

Southern California.

Over the next few days as Adamski gradually

revealed details of his meeting with the bed-ridden pope, and produced

evidence to support its authenticity, it became apparent that the

fakir of flying saucers had pulled one of his biggest rabbits out of

the hat.

Before he said goodbye to Zinsstag they had a last intimate talk.

Adamski spoke with a depth and power that she has never been able to

put into words – referring to it simply as “our last private

conversation.” She came away with an unshakable belief in his

legitimacy and stature, but not so much that it dulled her

discrimination. Eleven months later she resigned from Adamski’s

network in dissatisfaction over his claims and contradictions.

Adamski flew to London for his last days with Leslie. George had

changed, but not in the way that Zinsstag had noticed. “There was a

greater calmness, a heightened spirituality, and the traces of

tiresome egotism that had annoyed me ten years earlier had entirely

disappeared,” Leslie noted later. “He was as one who had experienced

the ultimate mysteries, and no longer cared whether he was believed or

disbelieved. He knew.” Perhaps Adamski “knew” when he was relaxing in

the warmth of admiring friends. Seven months later when he was being

called to account for dishonesty he lost sight of the ultimate

mysteries. On 13 December he wrote a dishonorable letter to a Canadian

correspondent shifting blame to others for a fake mail-based scheme

that he had helped mastermind. Much of his mail in late 1963 and early

1964 involved attempts to extricate himself from tight spots that had

their seeds in 1962; his letters swirled with craft and indignant

self-justification.

The Government Cottons On

Some time during the Adamski years, MJ-12 (or whatever they were

calling themselves at the time) came to realise that he was the real

McCoy, someone who was having genuine repeat ‘contacts.’ The

realisation may even have occurred as early as the 1952 Desert Center

encounter. Throughout much of that event, military aircraft were in

the skies above Adamski and his group, clearly alerted by tell-tale

radar returns from the cigar-shaped ‘mothership’ and possibly the

bell-shaped craft that touched down. It would have been easy for

analysts to put two and two together, to tie in this military alert

with the subsequent newspaper publicity surrounding Adamski’s claim of

a face-to-face meeting.

After his link-up with George in 1957, Carol

Honey began to find that his mail was being intercepted. His most

sensitive papers relating to UFOs and Adamski, which were kept locked

away, were expertly stolen. The burglary left no trace and no

indication of when it had occurred. All the documents “disappeared at

some time unknown to me, since I did not check on them very often,”

Honey wrote later. “No signs of a break-in were found to the residence

or to the cabinet.” Government intelligence operatives would

periodically turn up at his work and interview him about his and

George’s latest activities. “I was always treated courteously and was

never threatened in any way. They always acted as if they knew my

claims were real and not imaginary.” The Steckling family, in

Washington DC, who forged a close friendship with Adamski, were often

visited by intelligence agents. The Rodeffers, in nearby Silver

Spring, where Adamski stayed, had their phone tapped and their mail

opened.

In 1960, Adamski reportedly invited both presidential candidates to

visit him during their primary campaigning in California. Richard

Nixon declined but Senator John F. Kennedy accepted, according to

Glenn Steckling. Steckling, a professional aviator, now has control of

Adamski’s personal papers, tapes and literary estate through the

George Adamski Foundation that Alice Wells set up. Steckling also had

access to the reminiscences of both Wells and Ulrich who his family

helped care for in their old age. The meeting with Kennedy is said to

have been held in secrecy in George’s Carlsbad home. If a link was

forged with the future president, there may have been some substance

to later claims of occasional meetings between the two. Whether useful

information was ever passed across at these confidential tete-a-tetes

will probably never be known.

One would have to question if anything

of value was transmitted at a meeting Adamski had in Washington in

April, 1962, hard on the heels of the ‘Saturn Trip’. He returned from

‘outer space’ imbued with an urgent impulse to pass on a confidential

message to the president. This had been entrusted to him by the space

people. Danish Air Force major, Hans C. Petersen, Adamski’s co-worker

in Denmark, was based in Washington at the time working in the Danish

NATO exchange office. He received a call from Adamski with the hot

news. “He called me right away after he came back,” said Petersen in

1995, “and told me that he had to go to Washington on his arrival

because he had a message to the President, ‘but,’ he said, ‘I cannot

tell you what this message is. But if you follow the political

situation of the Earth you will, for yourself, be able to see what the

message contains. In one year you will see the result.’” Petersen was

one of Adamski’s most devoted followers and formed a rose-tinted view

of the message that was passed on.

He concluded afterwards that it was

a warning about the forthcoming Cuban missile crisis, a warning which

enabled Kennedy to resolve the nuclear-tipped stand-off with complete

mastery and the avoidance of violence. Apart from the fact that the

crisis occurred seven months after Adamski’s ‘warning’ rather than one

year later, there is nothing in any of the voluminous writings on the

missile crisis to suggest that Kennedy and his administration were

caught by anything but surprise by the Russian establishment of

missile launching sites in Cuba. The skillful way the crisis was

resolved by Kennedy was not the result of slick application of inside

information passed on from ETs, but by his acceptance of the best

recommendation that came from a special advisory group he set up that

wrestled for days and nights, in Kennedy’s absence, with an

ever-changing array of possible military and diplomatic responses.

There is no indication in the public record that either Kennedy or his

administration benefited from any type of foreknowledge, apart from

their long established practice of photo reconnaisance flights over

the controversial Caribbean nation. Nor is there any indication from

Adamski’s writings at the time that he was the bearer of a message

about an impending crisis. “My recent trip to Washington was very

successful,” he wrote to his co-workers afterwards. “I fulfilled the

mission I was assigned with good results. It was in reference to the

use of space for peaceful and educational purposes. I am well

satisfied with the response, even though it was costly to me from the

financial angle.”

Glenn Steckling says that apart from the Carlsbad talk, Adamski’s

other secret meetings with Kennedy occurred at the White House and at

Desert Hot Springs, in California, not far from Adamski’s home. (The

President is known to have visited the Hot Springs-Palm Springs area

four times in 1962-63, mainly for romantic dalliances.) Did the

meetings with Kennedy really occur? As Desmond Leslie said in his

Adamski obituary, “With George – anything could happen.” Certainly,

late in his life Adamski was the bearer of official passes that

indicated a close relationship with officialdom. William Sherwood, an

optical physicist and senior engineer with the Eastman-Kodak Company,

was a friend of his who examined the Government Ordnance Bureau card

that Adamski carried and which gave access to military bases.

Sherwood

once had a similar pass himself and felt that Adamski’s was

unquestionably genuine. Fred and Ingrid Steckling were shown a White

House pass by Adamski that appeared to be genuine. He maintained to

confidantes that when it came to passing on information he worked

“both sides of the fence”, as he called it. In other words, he not

only passed on messages from the space people, he passed on messages

to the space people.

The Most Extravagant Demonstration

The evidence for the return of the space people into the very centre

of Adamski’s life is most sensationally illustrated by the Silver

Spring ‘fly-by’ of 26 February, 1965. This display, apparently

conducted to give Adamski and his friend Madeleine Rodeffer the chance

to get unparalleled movie evidence, was the most extravagant

demonstration ever laid on for their man in a public place. Coming, as

it did, two months before his death it can perhaps be seen as a

touching valedictory and, in its own quirky way, some sort of

exoneration, or at least redemption. Hey, I know I screwed up for a

while, George might have said, but at least at the end I was back on

track, I still had the magic touch. How else to explain the

extraordinary events of that day?

Madeleine and Nelson Rodeffer were respected residents in a leafy,

low-density suburb of Silver Spring, Maryland, on the outskirts of

Washington DC. Here, the houses are set amidst large tree-covered

lawns on gentle, rolling contours. Nelson was a maintenance supervisor

at the Army’s Walter Reed Hospital in the Capital. Madeleine, a woman

of 42 at that time, had worked in the Army Finance Office during the

war and later acted as a doctor’s receptionist. She had helped

organise some speaking engagements for George on the East Coast a year

before and, together with her husband, had formed a firm friendship

with the veteran campaigner, so much so that when in their

neighbourhood he preferred to stay with them rather than in a hotel.

All those who met Mrs Rodeffer found her to be an impressive witness,

a woman of humility and gentleness whose account of that remarkable

day did not change at all in the years until her passing in June 2009.

Nelson had gone to work by the time Madeleine got up that morning. She

had recently broken a leg and was limping around in a plaster cast.

When she came downstairs Adamski had some news for her. Chalk up ‘Zany